U P C o mi n g :

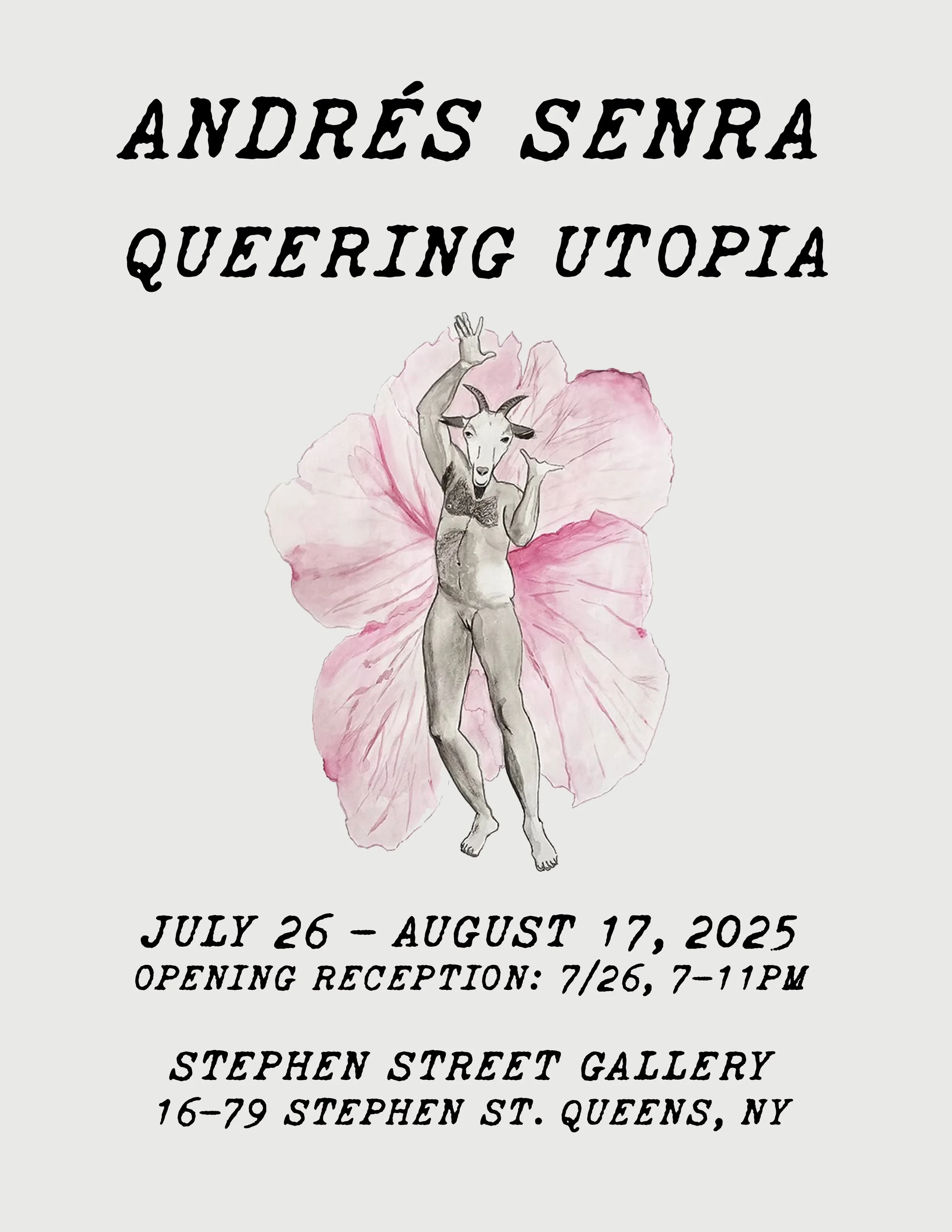

‘Queering Utopia’

Andres Senra

July 26 - August 17, 2025

Opening Reception: July 26, 7-11pm

Gallery open by appointment

This work began as part of an artist residency at the LMCC Arts Center on Governors Island. The project narrates the creation of a queer human-nonhuman AI utopia in a post-apocalyptic world following a global environmental crisis. Through speculative fiction, it highlights how cishetero patriarchy and colonialism led to the domination and exploitation of the planet by humans. It imagines a future with new intertwined relationships among humans, nonhumans, technology, and nature from an eco-queer perspective. The project is part of a series of Andrés Senra's latest works on queer futurism, featuring concepts of hybridization, cyborg theory, trans-species and inter-species relationships, and gender-fluid beings. The storytelling results from a conversation between Andrés Senra and an AI.